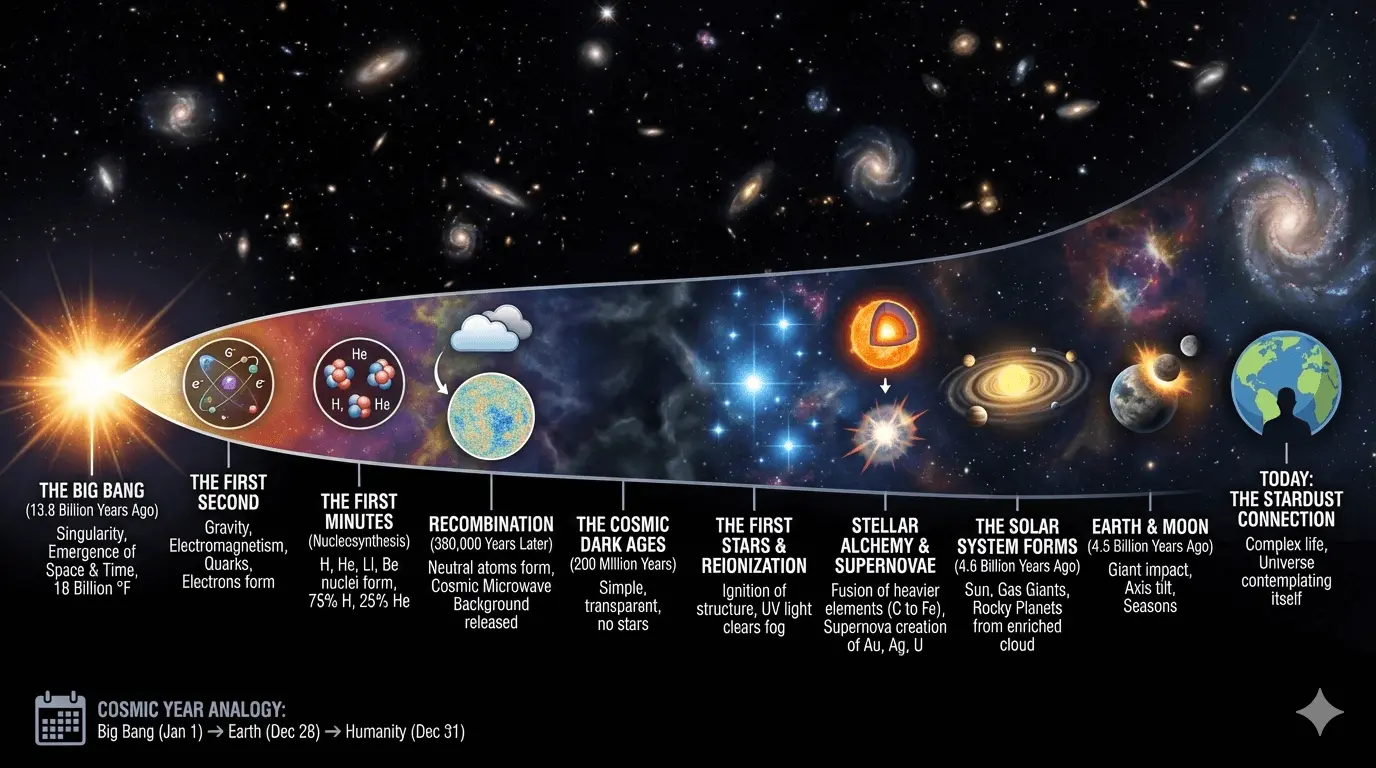

The Beginning: When Space and Time Were Born

Imagine a silence so complete that even the idea of distance does not exist. No clocks. No motion. No matter. No energy.

Then, around 13.8 billion years ago, that silence ended.

The universe came into existence in an event known as the Big Bang. This was not an explosion within space, it was the creation of space and time themselves. In that opening instant, all the matter and energy that would ever exist was compressed into a singularity, an unimaginably dense and hot state and temperatures estimated at nearly 18 billion degrees Fahrenheit.

Physics, as we know it, cannot yet describe what came before this moment—or why it happened at all. Those questions remain open. What science can do is reconstruct what happened next, and those first transformations determined everything that followed.

Big bang (Image credit: NASA)

The First Second: Forces Take Shape

Within the first fraction of a second, the newborn universe expanded and cooled just enough for structure to begin emerging.

The fundamental forces separated.

- Gravity broke away first, becoming the force that would later sculpt stars and galaxies

- Electromagnetism emerged soon after, laying the groundwork for atoms, chemistry, and eventually biology.

As space expanded, pure energy condensed into the first subatomic particles: quarks and electrons. At this stage, the environment was still too hot for anything stable to hold together, yet the cosmos was no longer formless, it was now governed by precise mathematical laws, laws that still operate today.

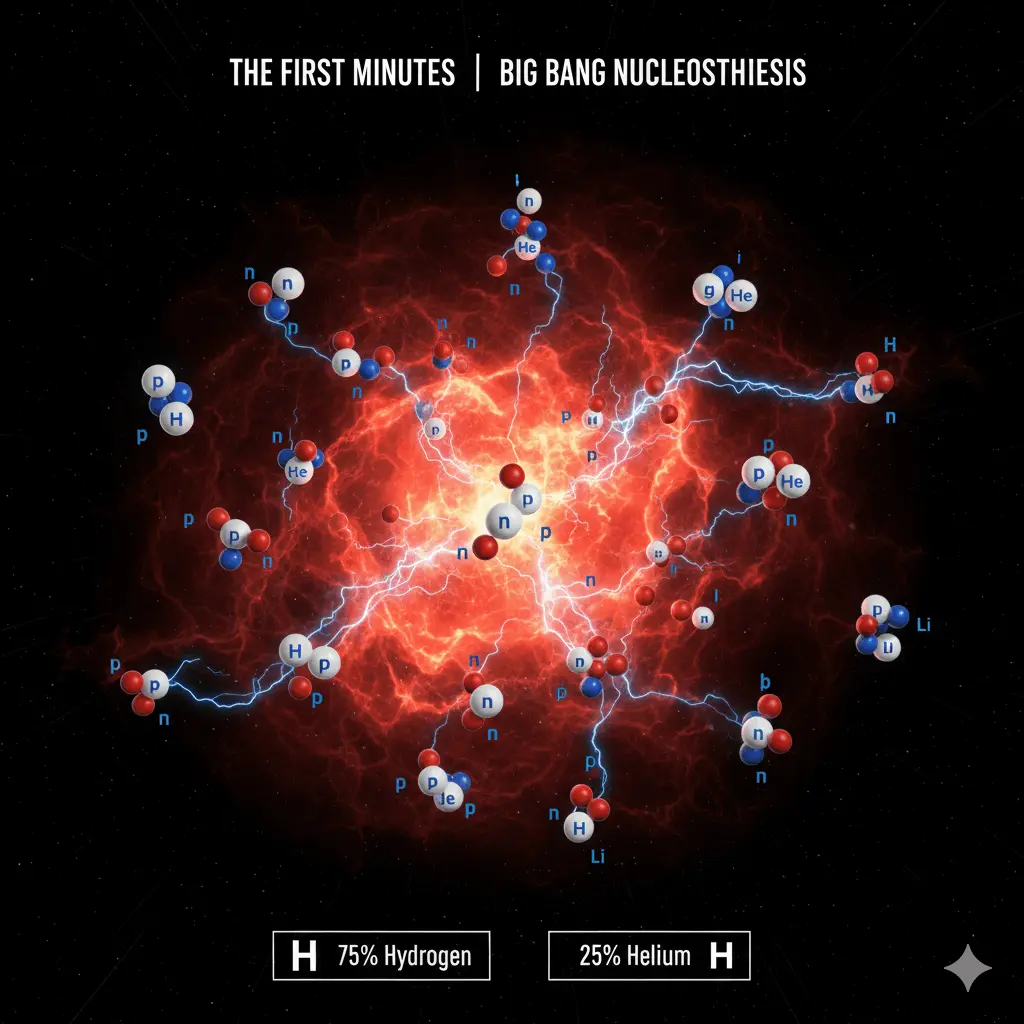

The First Minutes: Big Bang Nucleosynthesis

As expansion continued, temperatures dropped rapidly. Within the first three to five minutes, quarks began binding together to form protons and neutrons. These particles collided and fused in a brief but decisive process known as Big Bang nucleosynthesis.

This short window produced the universe’s first atomic nuclei:

-

Hydrogen, consisting of a single proton

-

Helium, made of two protons and two neutrons

-

Small traces of lithium and beryllium

Fun fact: if you check periodic table above elements are numbered in sequence from 1 to 4

By the time the universe was five minutes old, the “fusion factory” closed as temperatures fell too low to sustain the reaction. the universe had already locked in its basic composition 75% hydrogen and 25% helium, proportions we still observe in the deep cosmos today.

No heavier elements could form yet. The universe would have to wait.

380,000 Years Later: Atoms and the First Light

For hundreds of thousands of years, the universe remained hot, dense, and opaque. Free electrons scattered photons constantly, preventing light from traveling freely. Space was filled with a glowing plasma - a cosmic fog.

Then came a turning point.

Around 380,000 years after the Big Bang, temperatures dropped to approximately 3,000 Kelvin, allowing electrons to bind to atomic nuclei. Neutral atoms mostly hydrogen and helium formed for the first time. This event, known as recombination, made the universe transparent.

Light was finally free to travel.

The faint glow released at that time still exists today as the cosmic microwave background, the oldest light we can observe.

The universe was now transparent—but it was also completely dark.

The Cosmic Dark Ages: Simplicity Without Light

For roughly 200 million years, no stars or galaxies existed. The universe was dark, silent, and simple composed almost entirely of hydrogen and helium atoms drifting through expanding space. This era is known as the Cosmic Dark Ages.

Yet the universe was not perfectly uniform. Tiny variations in density—seeded by quantum fluctuations in the early universe were embedded within this simplicity.

These tiny ripples allowed gravity to begin its work.

The First Stars: When Gravity Ignited Light

The biggest early stars released iron-rich material when they exploded. By studying the makeup of later stars, astronomers can learn what those earlier stars were made of. (Image credit: National Astronomical Observatory of Japan)

Gravity amplifies even the smallest imbalance.

Regions that were slightly denser than their surroundings began pulling in more matter. Vast clouds of hydrogen and helium collapsed inward, heating as gravitational energy converted into thermal energy.

When the cores of these clouds reached temperatures of about 10 million degrees, a critical threshold was crossed.

Nuclear fusion ignited.

Hydrogen nuclei fused into helium, releasing enormous energy. Outward pressure from fusion balanced gravity’s inward pull, stabilizing the structure.

The universe’s first stars had turned on.

These early stars were immense often dozens or hundreds of times more massive than our Sun and extraordinarily luminous. They burned through their fuel quickly, ending the Dark Ages and flooding the universe with light. Over time, stars gathered into chaotic, merging systems: the first galaxies.

Reionization: The Universe Clears Again

The intense ultraviolet radiation from these young stars began stripping electrons from surrounding hydrogen atoms, a process known as reionization.

By roughly 1 billion years after the Big Bang, most hydrogen in intergalactic space was ionized. Light could once again travel freely across vast cosmic distances.

The universe had transitioned from darkness to illumination, from simplicity to structure.

But it was still chemically poor.

Stellar Alchemy: Building the Periodic Table

The early universe lacked the chemical diversity required for planets. To create the complex world we know, the universe needed a forge: the heart of a dying star.

As stars exhausted their hydrogen fuel, their cores contracted and heated further, enabling new fusion reactions. In massive stars, fusion proceeded in stages:

-

Helium fuses into Carbon (the basis of life).

-

Carbon into Oxygen (essential for water).

-

Oxygen into neon

-

Neon into silicon

-

Silicon into iron

Each step required higher temperatures and pressures, producing heavier elements essential for planets and life.

Iron marked the limit. Fusing iron consumes energy rather than releasing it. Once a star’s core filled with iron, fusion could no longer counter gravity and gravity wins instantly.

Supernovae: Creation Through Destruction

A single supernova can briefly outshine an entire galaxy, forging many of the heavy elements that eventually become planets and life itself. (Image credit: ESO/L. Calçada)

When gravity finally won, the star’s core collapsed in seconds. It rebounded violently, sending a shockwave outward that tore the star apart in a supernova explosion.

For a brief moment, a supernova can outshine an entire galaxy.

In these extreme conditions, rapid neutron capture created elements heavier than iron—gold, silver, uranium, and many others. The explosion scattered these elements into space, enriching future generations of stars and planetary systems.

The universe was no longer chemically simple. It had become fertile.

The Solar System: A Late but Fortunate Arrival

Around 4.6 billion years ago, nearly 9 billion years after the Big Bang, a cloud of gas and dust, enriched by ancient supernovae, collapsed in a quiet region of the Milky Way.

-

At its center, the Sun formed. Around it, a rotating protoplanetary disk took shape.

-

In the cold outer regions, ices and gases formed the giant planets

-

Closer to the Sun, metals and silicates formed rocky worlds

Through collisions and accretion, planets emerged.

Earth and the Moon: A Violent Beginning

Earth’s birth was violent.

About 4.5 billion years ago, a Mars-sized planetoid named Theia collided with the young planet (Earth). The impact vaporized both objects, ejecting debris into orbit that later condensed into the Moon.

This collision reshaped Earth’s destiny. It tilted the tilted Earth’s axis, gifting us the seasons, and stabilized our climate.

A Universe Built in Thresholds

If we compress the 13.8 billion years of cosmic history into a single calendar year:

- The Big Bang occurs on January 1st

- The first stars ignite in late January

- Earth appears in the final days of December

- Humanity arrives in the final seconds

We are late arrivals, but we are built from the very history of the cosmos. Every atom of calcium in your bones and iron in your blood was forged inside a star that lived and died billions of years ago. As we look at the night sky, we are essentially the universe looking back at itself, tracing a journey from a void of infinite heat to a world teeming with life.