Hey folks! 👋 Ever dealt with that frustrating feeling when two things try to happen at once, and everything ends up in a mess? That’s exactly what race conditions do in distributed systems! But don’t worry—today, I’ll walk you through how pessimistic locking steps in to save the day. We’ll keep things simple and easy to follow. Ready? Let’s jump in!

What’s a Race Condition? And Why Should You Care?

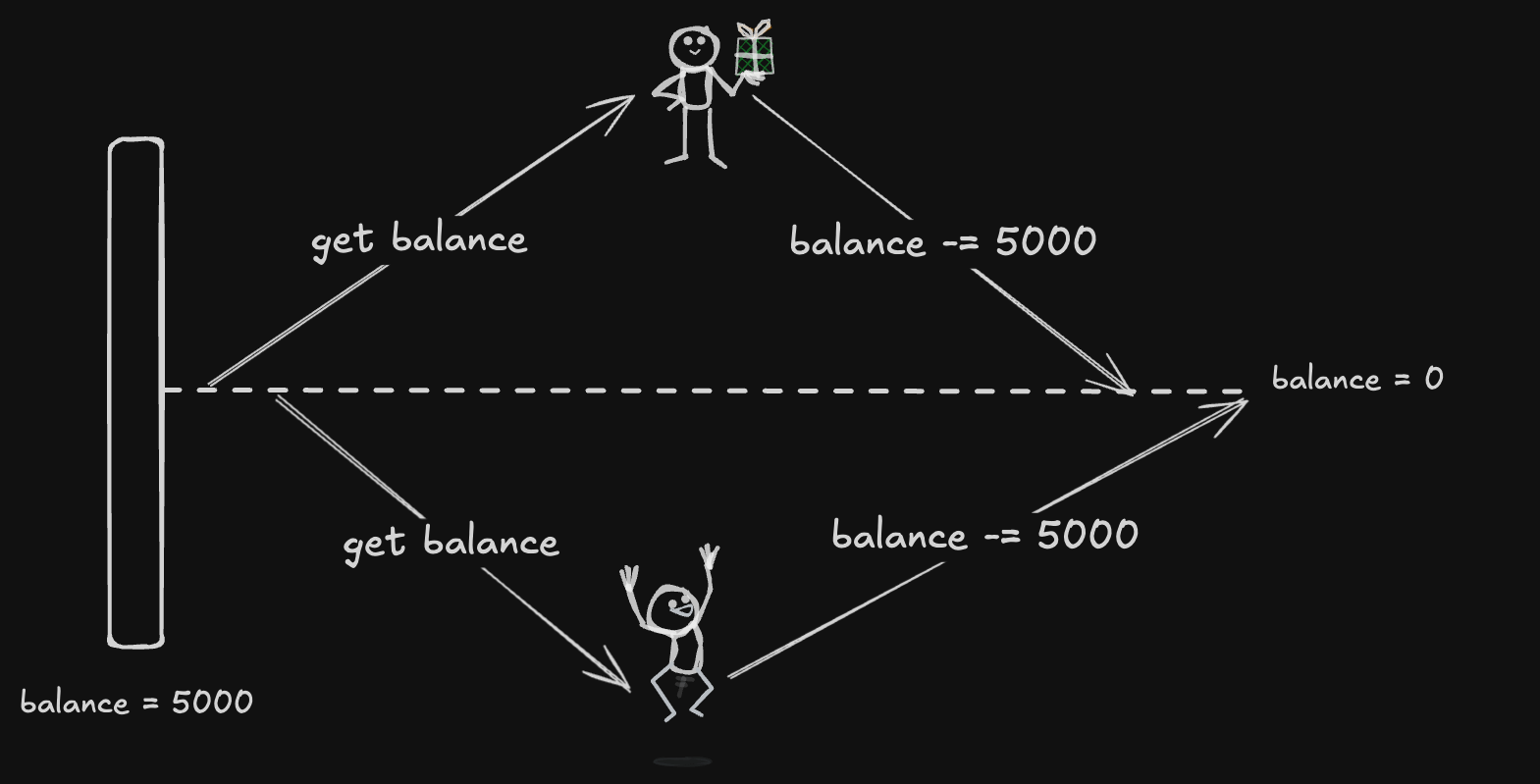

Imagin this: You and your friend both try to withdraw cash from the same account, at the exact same time. There’s only ₹5,000 in the account, but somehow, both of you manage to withdraw ₹5,000 each. That’s double the money! 🎩✨ While this might sound great at first, it’s a nightmare for banks and a perfect example of a race condition.

In tech terms, a race condition happens when two or more processes try to access or update the same data at the same time. If there’s no proper control, things can go wrong—like data getting corrupted or lost.

Distributed systems, where multiple services or nodes interact with the same data, are especially vulnerable to these issues. That’s where pessimistic locking steps in, acting like a bouncer at a club. 🚪

What Exactly is Pessimistic Locking?

Alright, let’s talk about pessimistic locking. Think of it as assuming the worst: “If I don’t block access to this data now, someone else will mess it up.” So, the system locks the resource upfront, preventing anyone else from touching it until the first process finishes.

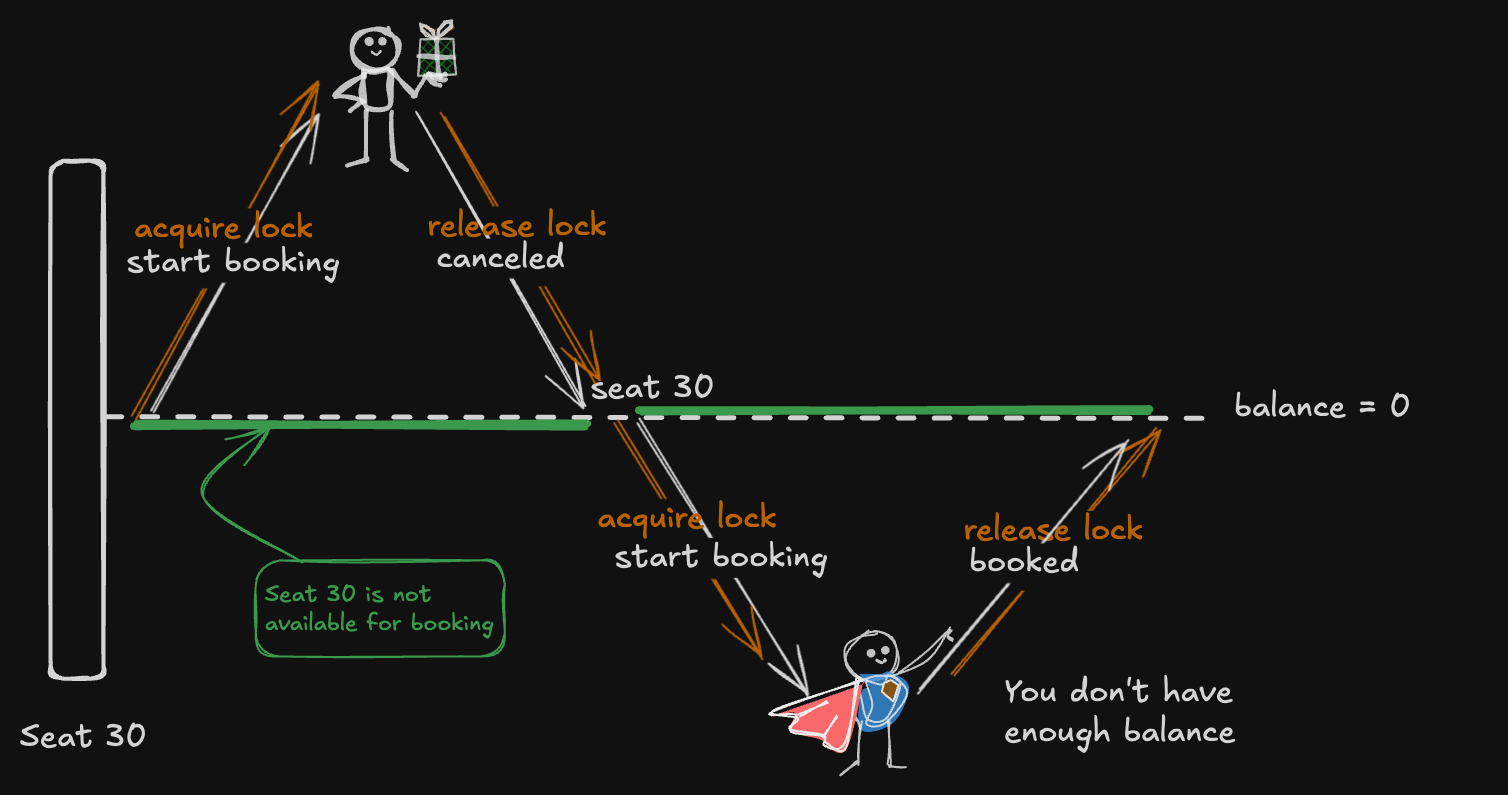

Imagine you’re booking a seat for a movie. As soon as you confirm the booking, that specific seat is “locked” for you—no one else can book it until your transaction is complete. The same logic applies in distributed systems. If one process locks a piece of data, all other processes have to wait patiently until the lock is released.

How Does Pessimistic Locking Work?

Here’s a quick breakdown of how pessimistic locking works when multiple nodes or services are involved:

1. Lock the Resource 🛑

- Let’s say Node A wants to update a record. Before it does anything, it locks the resource so no one else can touch it.

2. Exclusive Access 🔒

- While Node A holds the lock, other nodes (like Node B) can’t make changes. They’ll just have to wait until the lock is released.

3. Release the Lock 🗝️

- When Node A finishes its work, it releases the lock, giving other nodes the green light to proceed.

Pessimistic Locking in Distributed Systems

At a high level, locking in distributed systems works pretty much the same way as described earlier. But things get trickier because distributed systems have their own challenges—like node failures, replacements, or network partitions—which add complexity.

In these systems, a cluster-wide lock database keeps track of which node holds the lock on which resource. Every time a node acquires or releases a lock, this database is updated to reflect the change.

Acquiring a Lock is Just the Start — Lease Matters

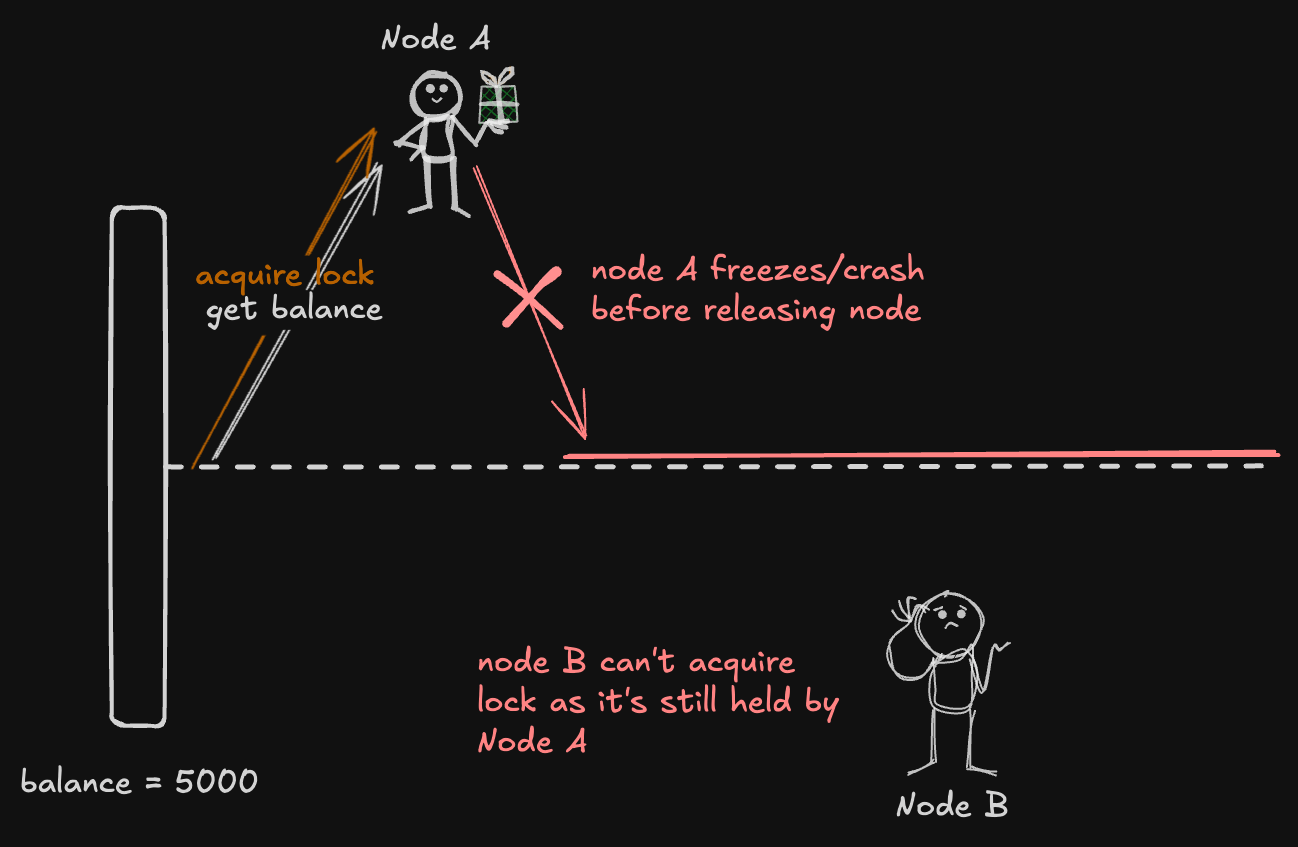

Let’s say Node A locks a shared resource (like an account balance) to update it. But right after acquiring the lock, Node A crashes or gets stuck, leaving the lock hanging. Now, other nodes (like Node B) trying to access the same resource are stuck waiting indefinitely because the system thinks Node A still holds the lock.

This is where timeout handling saves the day! ⏲️

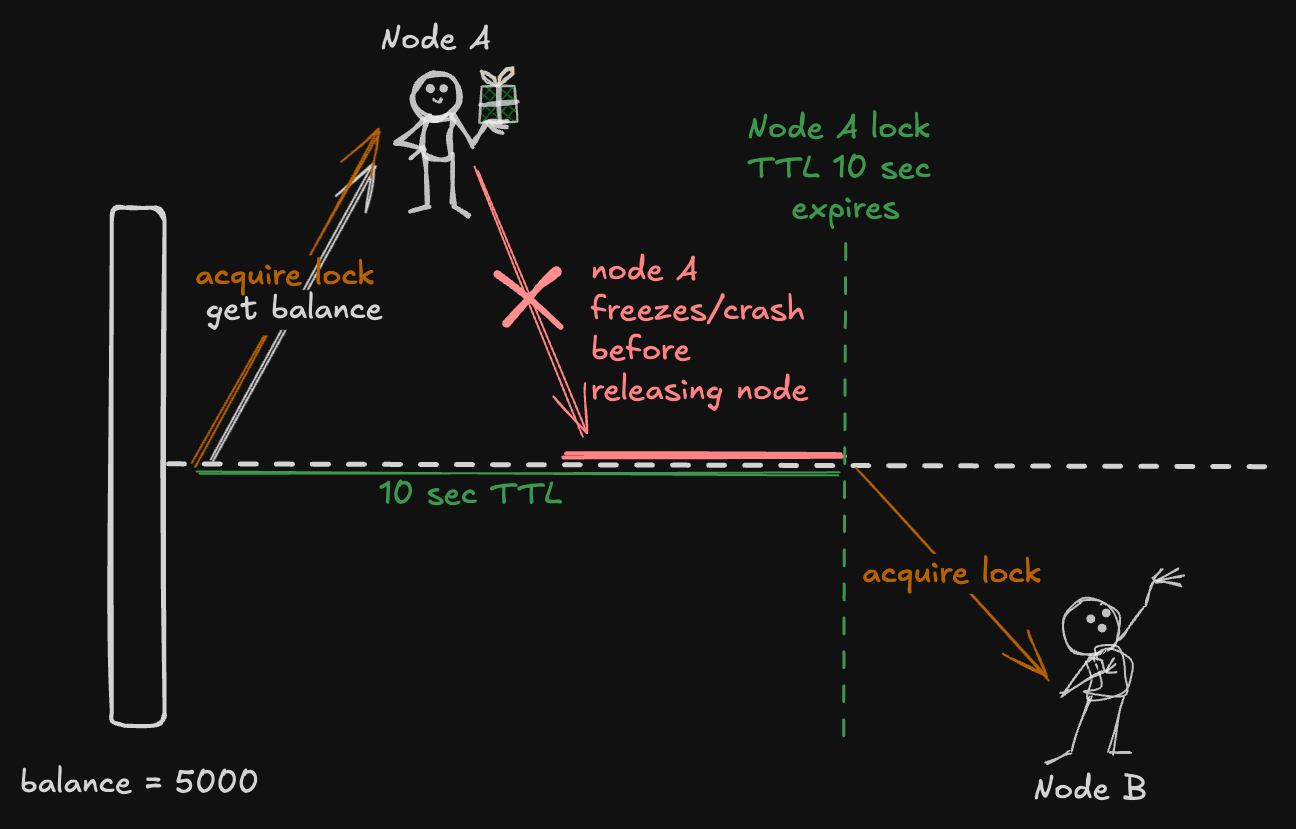

1. Setting a Timeout:

- When Node A acquires the lock, the system assigns a timeout value say, 10 seconds. This means that if the node doesn’t release the lock within 10 seconds, the system will automatically release it.

2. What Happens if Node A Crashes?

- If Node A crashes before releasing the lock, the timeout kicks in. After 10 seconds, the system assumes something went wrong and frees the lock.

3. What Happens Next?

- Now that the lock is released, Node B (or any other waiting node) can jump in and acquire the lock to access the resource safely.

Why Timeout Handling is Important

Without a timeout mechanism, the system could get stuck in a deadlock if the lock isn’t released. With timeouts in place, the system stays healthy, and processes don’t have to wait forever.

In real-world distributed systems, dynamically adjustable timeouts are often used to match the complexity of the operation—longer for intensive tasks and shorter for quick ones. This ensures a good balance between performance and safety.

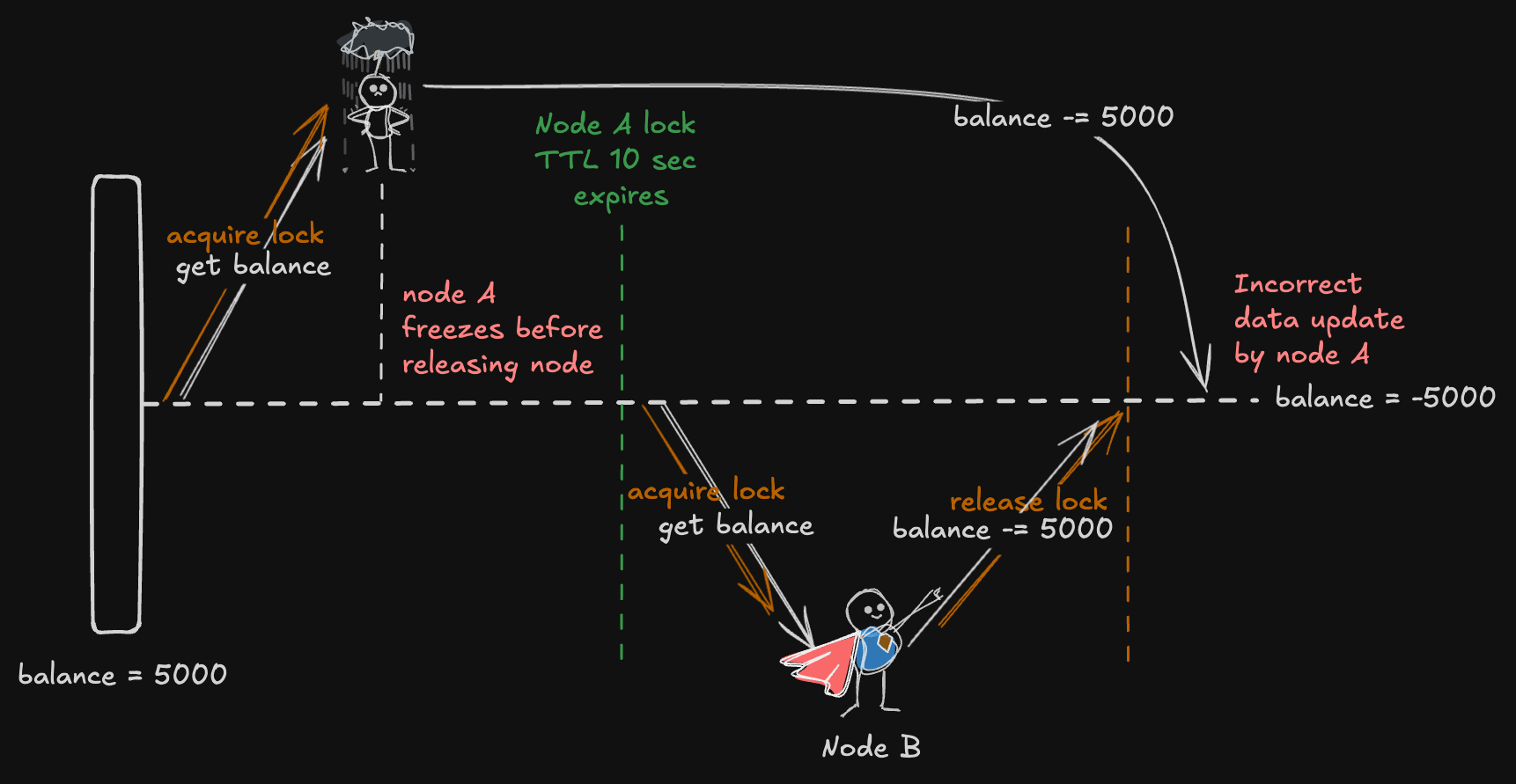

Scenario: Node Pauses, Resumes, and Causes Stale Updates

Imagine Node A acquires a lock on a shared resource (e.g., a user’s account balance) and starts processing some updates. But suddenly, Node A gets paused—maybe due to a network glitch or a system delay (like being swapped to disk). While Node A is paused, Node B steps in, notices the lock has expired (thanks to the timeout), acquires the lock, and updates the resource with new values.

Later, Node A resumes, unaware that the lock it held is no longer valid. It continues from where it left off, thinking it still owns the lock, and overwrites the changes made by Node B. This creates a stale update issue, leading to data inconsistency.

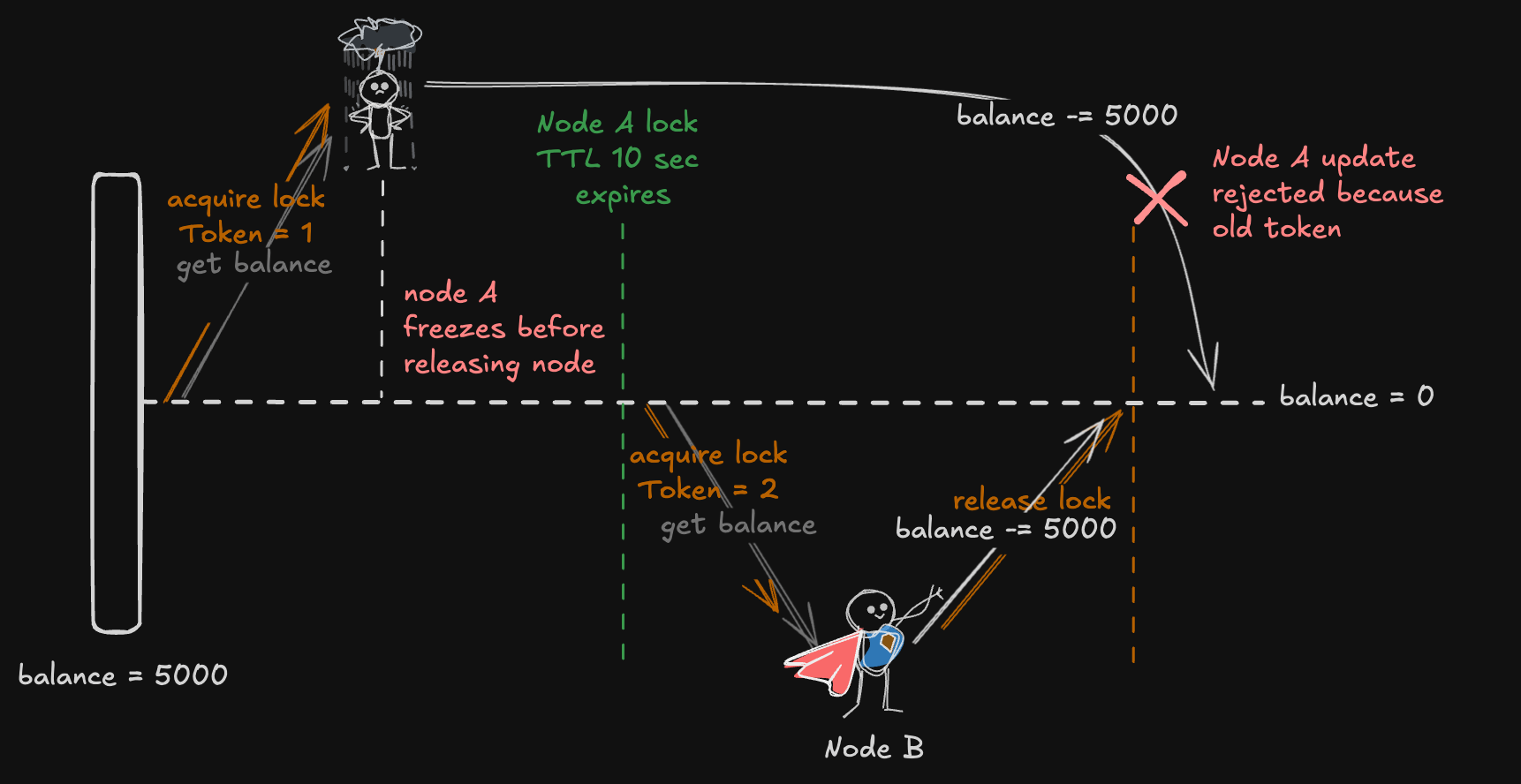

Fence Tokens Helps to Avoid Stale Updates

A fence token is like a version number or unique ID that increments with every lock acquisition. Here’s how it helps prevent stale updates:

1. Lock Acquisition with a Fence Token:

- When Node A acquires the lock, it receives Fence Token = 1.

- After Node A is paused and Node B acquires the lock, the system increments the token, and Node B gets Fence Token = 2.

2. Including Fence Token in Updates:

- Every time a node makes a change to the resource, it sends the fence token along with the update.

- The resource only accepts updates if the fence token matches the latest version it knows about.

3. Node A’s Resume and Attempted Update:

- When Node A resumes and tries to push its stale updates, it sends Fence Token = 1.

- But the resource knows the latest valid token is 2 (from Node B’s update), so it rejects Node A’s stale update.

Using fence tokens ensures that even if a node resumes after being paused, it can’t overwrite more recent changes. This prevents stale data from creeping into the system, keeping the data consistent and reliable. It’s a simple yet effective way to handle issues that timeouts alone can’t solve.

This approach is often used in distributed databases and systems to maintain strong consistency, especially in environments prone to delays or unpredictable pauses.